Author Archives: Marcel

Making EFL Matter Pt 1: Goals

As I write this, high school teachers across Japan are busy writing or polishing up “Can do” targets for the students at their school, in compliance with MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Science & Technology) requests. The purpose is to get schools and teachers to set language performance goals for the four skills, goals they can use in creating curriculum and in evaluating progress. It is, from what I have hear, not going smoothly. There are many reasons for this, not least of which is the novelty of the task. The challenge is to take the current practice of basically teaching and explaining textbook content and expand on that by setting more specific targets for reading, listening, writing, and speaking. Most schools did not have, nor attempt to teach, specific writing, listening, and speaking skills. In fact, I think it is fair to say that most schools and teachers viewed English more as a body of knowledge to be memorized than as sets of sub-skills or competencies that can be taught and tested. Even reading, by far the skill area that receives the most attention in senior high, is rarely broken into sub-skills or strategies that are taught/developed and tested. So I see MEXT’s request as an attempt to break schools and teachers out of their present mindset; to get them to approach language teaching as a skill-developing undertaking, and to get them to focus on all four skills in a more balanced manner.

As you can imagine, responses to the Can do list requirement have been varied. Of course schools are complying, but the interpretations of the concept of a 4-skill rubric for three years with can-do statements for each skill in each year don’t seem to be uniform. Some see the can-do statements as goals–impossible goals for at least some of the boxes of the rubric. So one problem is that many of the boxes in the rubric (especially for listening, speaking, and writing) will be filled ad hoc, never to be really dealt with by the program. Another problem is that can-do statements as they are used in CEFR are not goals or targets, but merely descriptors. That is, they are meant to make general statements about proficiency. That is, even when schools do decide their can-do statements for the various boxes of the rubric, that will not be enough to make a difference. That’s because can-do statement can help inform in the setting of more specific targets at an institution, but they should not function as goals/targets themselves. A lot of people don’t get that, apparently.

That is to say, an important step is missing. In order to design curricula, very specific sets of sub-skills or competencies must be explicitly drawn up. These are informed by the guiding goals (can-do statements), but are detailed and linked to classroom activities that can develop them. Let’s say we are dealing with listening. Can-do statements for a second year group might include something like this: Can understand short utterances by proficient speakers on familiar topics. This statement then needs to be broken into more detailed competencies–linked speech, ellipsis, common formulaic expressions, different accents, top-down strategies, etc., for example–that then need to be taught and tested regularly in classes. This is something that is not happening now in most public schools.

At the crux of the problem is the fact that many (actually I think we can safely say most here) teachers do not have a clear idea of the exact competencies they are aiming for in each skill area. Instead, most teachers tend to think of a few key skills that they develop with certain textbooks or activities. The MEXT assignment to write a can-do rubric could nudge schools and teachers in a certain direction, but it is a rather hopeful nudge for a rather complex problem. It could potentially be a game changer. If every teacher had to sit together and come up with can-do statements and specific competencies that they would develop in each skill area, the impact on English education could be huge. But that is unlikely to happen. The process of going from here to there is rather complicated and long hours of collaboration and re-conceptualizing are necessary. Instead, schools are mostly assigning one unfortunate soul from the English department to do the whole thing him/herself. It is probably unrealistic to expect much change.

Actually, even if schools were to make good can-do rubrics and set specific target competencies, the real battle is only beginning. Making those targets clear to students and creating a system where learners are moving toward mastery is a tremendous challenge. According to Leaders of Their Own Learning, programs need to set knowledge, skills, and reasoning targets for students. These targets will necessarily come in clusters of micro-skills or micro-competencies. These are then reworded into can-do statements given to students at the beginning of each lesson, so students can know what they will be learning and how they are expected to perform. That’s a lot of writing, and it will require a lot of agreement to produce. And that can only come about after much discussion and conceptualization shifting and decision-making on the part of the teachers. But that’s not all. For these targets to work, everyone–teachers, students, parents, and administrators–must be on board. It is hard to imagine such vision and collegiality at public high schools in Japan.

The diagram above shows the process that Ron Berger and the other authors of Leaders of Their Own Learning recommend to improve student performance. Goal-setting is only one part of this, but it is an essential part. Without goals, none of the other activities are possible. In subsequent posts, I’ll be looking at some of the other parts, and some of the other ways that teachers and administrators can improve education.

This post is part of a series considering ways to add more focus and learning to EFL classrooms by drawing on ideas and best practices from L1 classrooms.

Part 2 looks at the use of data and feedback.

Part 3 looks at the challenges and benefits of academic discussions

Language on Stage: Debate and Musicals

In his 2011 book Creative Thinkering, Michael Michalko explains the idea of conceptual blending. What you do is take dissimilar objects or subjects and then blend them–that is, force a conceptual connection between them by comparing and contrasting features. It’s an enlightening little mental activity that can help you to come up with creative ideas or insights as you think about how the features of one thing could possibly be manifested in another. In the past few days, I’ve tried blending two activities that I’ve seen push EFL improvement more than any other: performance in club-produced musicals, and competitive policy debating. I’ve compared them with each other and with regular classroom settings,

I chose these two because over the last few years I have seen drama and debate produce language improvements that go off the charts. This improvement can be explained partly in terms of the hours on task that both of these activities require and the fact that students elect to take part voluntarily, but I don’t think that explains everything. There are certainly other possible factors: both require playing roles; both are team activities; both have performance pressure; both reward accomplishment; both require multi-modal language use and genre transformation; both require attention to meaning and form; both are complex skills that require repeated, intensive practice to achieve, and that practice is strictly monitored by everyone involved, who then give repeated formative feedback. Not complete, but not a bad list, I thought.

But then while reading Leaders of Their Own Learning, a wonderful sort of new book by Ron Berger, Leah Rugen, and Libby Woodfin, I came across this quote by a principal of a middle school in the US:

“Anytime you make the work public, set the bar high, and are transparent about the steps to make a high-quality product, kids will deliver.”

I think the speaker hit the nail on the head as to why activities like debate and drama work: public, high expectations, and clear steps. Aha: public! The dominant feature of debate and drama is that there is a public performance element to them. Students prepare, keenly aware that they will be onstage at some point; they will be in the spotlight and they will be evaluated. Of course students need support and scaffolding and lots of practice before they can get on stage, but unless there is a stage, everything else won’t matter as much. It is the driver of drivers. Is that pressure this message suggests? Yup, but also purpose. I have seen kids transformed by the experiences of competitive debating or performing in a musical. I refuse to believe that the mediocrity I see in so many language course and programs is the way it has to be.

So, to get back to the whole reason for this little thought experiment: how can we take these best features of debate and drama and apply them to language programs? The key, I hope you will agree, is introducing a public performance element. There needs to be some kind of public element that encompasses a broad range of knowledge, skills, and micro-skills, and then there needs to be sufficient teaching, scaffolding, and practice to ensure public success. But how…?

Over the next few blog posts, I’ll be exploring these issues, drawing from ideas that are being developed in K-12 education in the US, particularly in approaches that have been working in high-challenge schools with English language learners and other at-risk learners (for example, by Expeditionary Learning, WestEd, and Uncommon Schools). In particular, I’ll be looking at ideas in Leaders of Their Own Learning (mentioned and linked above), Scaffolding the Academic Success of English Language Learners, by Walqui and Van Lier, and the soon-to-be-released second edition of Teach Like a Champion 2.0 by Doug Lemov. I’ll be looking at all of these through the lens of an EFL teacher in Japan. Many things in these books won’t be applicable in my context, but I suspect many may help inform ways of improvement here.

The Missing Link: How EFL can get to CLIL

In my last post way back in May, I suggested that a little bit of communicative language teaching (CLT) is unlikely to make much difference in high school English courses in Japan. My reasons were that just dabbling with CLT is not enough. It results in short, mostly unconnected utterances, and it rarely displays age or grade-appropriate thinking. The teachers are not used to this approach, even if they find it appealing on some levels–I mean, where is the high school English teacher who thinks that English shouldn’t be used for communication, at some point, somewhere? But it is not just warm feelings about a language that help decide what actually happens in classrooms. What teachers are used to, what they have been trained to do, and what just about everyone seems to expect them to to do, are also forces that shape the culture of teaching in Japan. Among them is little knowledge/experience or clear vision of how to give CLT more prominence in classrooms.

MEXT’s policies are actually pretty good, in my opinion (as limited as my perspective is). But the world of HS teaching is one of schools at vastly different levels, with vastly different types of students. Textbooks to be covered, (school, and entrance) exams on the horizon, and students increasingly distracted, are realities in teachers’ lives. A little CLT probably cannot do much to address these realities, even if it might be a little more pleasant than the norm now. What I think is needed is a new system, a system not organized by sequences of grammar structures but by sequences of performance skills and discourse/socio-cultural/linguistic knowledge. The goal should be to develop learners to the point where they can functionally continue to learn in English, gaining more detailed familiarity with the language and topics they need–in other words, get HS students to the point where CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) lessons are possible. This is an interim goal, to be sure, but after students can basically function in a CLIL classroom, they can further develop their familiarity and competence with content related to their needs/futures. You may be thinking that CLIL is an approach, a way of teaching language and content at the same time. How or why should it be a goal? Why not just go ahead and institute CLIL in high schools? Then you could have kids learning the language they need and the content, too. The problem with this is that it is not possible to just switch to a CLIL approach given the current mindsets and limitations of teachers. Sorry, but for many of the same reasons why CLT won’t fly even if you push it off the cliff, CLIL is impossible to just deploy in classrooms. Plainly put: you can’t get there from here.

I think CLT sometimes fails to gain traction because it is seen as a distraction from serious learning. Part of the reason is washback from entrance exams to be sure, but part is also the lack of perceived academic rigor of activities such as asking for directions, explaining your favorite dish, or inviting someone to a movie (or any of the many language functions commonly put in the eikaiwa column of teaching content. In my present job as a teacher trainer I regularly encounter this mindset. My colleagues and I find that the majority of teachers do not understand how reading can be taught communicatively, for example, since they have always thought of communicative language teaching as being all about speaking and writing. And now MEXT is suggesting a greater focus on productive skills and teachers are scrambling to try to make time to add just a little bit more to the status quo, a token bit of CLT. Will it be better than none? Absolutely. Will it result in the kind of integrative 4-skill lessons MEXT is aiming for? Well, the central mindset problem still remains: CLT is seen as a less-than-rigorous add-on to the “main” part of the lesson. Very, very few teachers know how to teach language integrated with content. Very, very few seem to be able to break down the essential skills into teachable chunks that can then be sequenced. Those few who do are doing it by inventing their own curricula. And they are pointing the way forward.

Come with me for a moment to a small mid-level high school in Gifu Prefecture. Let’s listen in on some students who are discussing Rosa Parks’s quiet act of subversion. Was she right to not stand up? What would you have done, and why? After students complete a mindmap of their opinions, they get into groups of four and begin discussing the topic. The students have been told that they should try to use words, phrases, or sentences from the textbook as reasons to support their opinions.

Student 1: So you would stand up because you are scared to arrested?

Student 2: Yes.

Student 1: Someone will…you…not you?

Student 2: Yes.

Student 3: No, no, no, no. I disagree with [Student 2]. If I were [Rosa Parks], I would not stand up.

Student 4: Not stand up?

Student 3: No.

Student 4: Why not?

Student 3: I’m scared to be arrested, too. It’s true. But…[she opens her text book]…please look at this page. She said, “One person can make a difference.” That means we should move. If she had given up her seat, Barak Obama may not be president of the United States

You must visit a large number of classrooms to realize how remarkable this activity is. The students are communicating–exchanging opinions about the textbook content–interactively. They are saying something. Not something as in anything, but supported opinions. They are listening actively to each other and building on each others’ ideas. This, ladies and gentlemen, is an academic discussion. It’s not perfect, and it shows only a few of many necessary skills, but it’s happening mostly successfully.

Discussions are big in L1 classrooms now in the US and many other countries. They are powerful tools for learning. They promote good thinking skills, good listening skills, social interaction skills, and language skills. The big question is: can EFL learners get the same benefits? The example above suggests that it is possible in a Japanese high school context. One example may not be all that convincing, but experience from the US suggests that language learners do benefit from this approach. Fisher, Frey & Rothenberg (2008) make the case of using content-area discussions for EFL learners. They also explain how to scaffold for these learners. Most of their activities include cooperative learning of some sort, and they show how through modelling, clear tasks and objectives, and careful support for less proficient learners, discussions can be a means of learning language and an activity that yields considerable academic benefits. As in the example above, students are trained how to act and interact. Talk is seen as a way of developing literacy, which facilitates the learning of reading and writing skills. Talk in groups comes with content and outcome goals, but also with language and social goals. The importance of this final point should be highlighted: discussions allow learners to learn much more than language, and much more than content. They learn how to learn with others, how to interact with others, and what to do when different ideas and opinions emerge in groups. These are, I’m sure you agree, important skills that are closely linked to language skills.

Zwiers and Crawford (2011) in another book on discussion focus on academic conversations. They identify key skills and show how to teach and train students in their use. Sometimes the words “discussion” and “debate” are thrown around in the world of language teaching. If you would like to know what skills are involved with discussion and debate, Zwiers and Crawford is a good place to start. We language teachers have been poor at identifying or focusing on the kinds of micro-skills that are needed for expression, disagreements, presentation, or interaction. Rather than seeing these things as skills that emerge naturally over time as our students gain proficiency, perhaps these skills can be used to drive the learning of language and thinking skills. In EFL settings, we should be pushing our students to think better, interact better. Zwiers and Crawford are concerned only with the L1 classroom. Not everything will be teachable to EFL classes in Japan, but much will, and the potential benefits are certainly there. It seems to me that these benefits are also prerequisite skills for CLIL classrooms. Unless students are ready and able to engage with the content and each other, any CLIL lesson will be dead in the water.

This post may not have convinced you of the importance of heading toward CLIL-type lessons at the high school level, or the necessity of developing discussion/conversation skills to reach the point where CLIL is possible, but I hope it has given you something to think about. CLT without more rigorous thinking and opportunities for use seems unlikely to improve the state of English education in Japan. Content-focused academic discussions (along with presentations and debates) is an attractive option, I believe, though certainly not one that will be easy to implement. Like the teacher whose students we met above, we have a lot of curricula to develop.

Is CLT the Right Approach for Japanese High Schools?

In 2013, I observed a sample lesson at a middle-level high school in Japan. The purpose was to demonstrate a style of lesson and convince the attending English teachers to emulate it. One of the targets of emulation was teaching English in English, and the other was teaching English communicatively. Dozens of English teachers from across the prefecture were there, dutifully and cautiously observing the sample lesson, in which a teacher managed to conduct a textbook unit explanation and lead a productive task almost entirely in English.

Few doubts or complaints were aired by the observing teachers. They know which way the wind is blowing. They know that the education board staff running the lesson observation/training have an agenda, and that agenda comes down from the Ministry: teach English in English; do productive tasks; teach communicatively. They understand that it is something that they should probably be doing, even though they did not experience this type of lesson themselves as students, even though they were never really trained to teach this way in college teacher training courses or on the job, even though they have doubts about their own English competence and are reluctant to put their shortcomings on display too much. So, they nodded politely, and promised to take the ideas back to their schools for further consideration.

Where, of course, it would be back to business as usual.

Nishino (2009) produced a paper that I still have trouble comprehending, but which I believe continues to sum up attitudes to teaching English communicatively in high schools in Japan. She found that Japanese teachers have pretty positive attitudes toward communicative language teaching (CLT), but mostly choose not to engage in it themselves. The reason, I guess, comes back to the lack of experience, training, and language proficiency on the part of teachers. But in my present position, it is my job to promote a greater use of English in the classroom by teachers and students, and that naturally involves more communicative activities.

For most Japanese teachers of English, however, this goes against their strengths, which often include techniques for grammar and vocab explanation, classroom management skills, and a proficiency with tasks that raise awareness of language features and encourage memorization. The CLT techniques my group (and the Ministry, and the BOE) are recommending often seem less than exemplary when observed in real classrooms, despite the authority of SLA research that stands behind the approach. This becomes painfully obvious when it is put on display, as in the class mentioned above, where the teacher had students write a short opinion about the topic and then share it with a partner and then the whole class. Even I couldn’t help thinking that the intellectual level was pretty low, and the pace was very slow. I’m sure many of the teachers observing with me had the following thoughts going through their heads: this is dumb and really inefficient.

And this brings me to the main point of this post. The dabbling with CLT that I have seen in classrooms here makes me wonder if it is worth the effort of teacher awareness raising, of teacher skill training, particularly if we see it as a goal unto itself. It seems that a little more CLT in classrooms is unlikely to make much of a positive difference in language classrooms. Students don’t seem especially more engaged, and the trite bits of incorrect language that often get produced are depressing–and are often incomprehensible to other students without a quick translation from the teacher. I know that the system is failing pretty much at producing kids who can use the language right now. But I don’t think the fix will come with a few more CLT activities and a strict English-only policy on the part of teachers.

Of course, the answer cannot be business as usual either. Teachers have been yakking at students for years, explaining and translating, and that hasn’t worked out well at all. Van Patten (2014) in Interlanguage Forty Years Later, is particularly blunt in his assessment of the teaching of language by the teaching of rules, the kind most common still in Japan: “competence is not derived from explicit instruction/learning…[and that] holds true for all learners and all stages of development…” (pg. 123). Yes, instruction gets you something, but it is not competence. Form-focused instruction is very limited in what it can do for language learners, that much seems obvious to everyone–well, almost everyone….

So what it is the answer? I’m not sure, but more language, more language use, and more focused teaching seem to be the only way forward. Standing in the way, though, are the lack of proficiency of teachers (along with their lack of training/familiarity with alternative approaches), the culture of expectations that makes change difficult (the parents, the cram schools, the perceptions of entrance exams, the publishers, etc.), the passivity of students and their unfamiliarity with the kind of active use of the language needed to leverage learning, and the well-meaning souls whose hearts warm satisfactorily when students produce any kind of utterance (even when it is intellectually low, and mostly incomprehensible). Framed another way, what we need is more language processing and more responsibility for doing so in a comprehensible and academically appropriate manner.

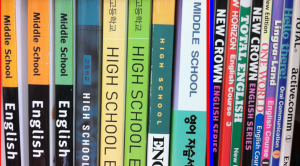

The image above (from a presentation on vocabulary by Rob Waring) shows a bookshelf with Korean English textbooks on the left and Japanese ones on the right. Notice the size difference? That translates to Korean students being exposed to thousands of words more during their years in mandatory education. The poverty of input argument for Japan is pretty easy to make if we look at just the amount of language students are exposed to, compared to Korea or Mexico (as Mr. Waring did), both of whom now handily beat Japanese scores on high stakes tests (TOEFL iBT, 2013: Japan 70, Korea 85).

There may be other reasons why Korean TOEFL test scores are higher. But certainly language exposure is one of them. Perhaps it is time to admit that in Japan, teachers explain too much in Japanese about too little target language. Adding a little “communicative” jibberish to that is unlikely to make a big difference, and may actually be detrimental in the long run if it lowers expectations further. In my opinion, more language immersion in the form of CLIL-type lessons at the high school level might be an interesting option to explore , since it provides CLT with sufficient input, thinking rigor, and responsibility.

Repeat After Me: It’s the Feedback

The other day I observed a few lessons by a very good Japanese English teacher at a junior high school. At one point in the lesson, while the students were reading the textbook passage out loud, she walked around the classroom with two pads of post-it sticky notes, one green and one pink. As she listened to the students, she gave them pink notes for parts they did especially well, and green notes for parts they were having trouble pronouncing. On each note she wrote a specific phrase, word, or part of the word the students were either doing well or needed to improve. And at the end of the class, she made some general comments and engaged the students in a little extra practice of specific pronunciation errors that many students were making. Each student who received a green note, however, was responsible for coming up to the teacher after class and demonstrating that they could produce the sound correctly.

I was deeply impressed for a couple of reasons. First, because this is the first time in three years and dozens of observed EFL lessons that I have seen a teacher do this. It was great to see a class that dealt with pronunciation at all; and it was especially impressive to see a Japanese teacher deal with pronunciation in this manner. Too many JTEs ignore that fact that English, like any language, is first and foremost a system of sounds. The written form dominates language lessons in Japan, where learning English has traditionally meant essentially learning to read English. Listening activities usually consist of listening to the blocks of audio that just verbalize the text content. And I think it’s fair to say that most JTEs won’t go near pronunciation in a class without an ALT or a CD ready to model the “correct” pronunciation. It takes confidence, and it takes an acceptance of the view that a JTE is a valid example of language use in the classroom–language as sounds, language as culture, language as a means of communication, all of which the teacher displayed nicely. And second, this teacher demonstrated something that is incredibly important in pronunciation learning (and indeed in all of language learning): formative feedback.

For any type of learning, it is essential that people can see what they need to do (a model), can give it a try (practice), receive feedback on their performance or learning (formative feedback), and then get a chance to do it again to correct problems. Of particular importance is the feedback loop of performing a skill or demonstrating knowledge and then receiving quick, actionable, formative feedback that can immediately be used to make improvements. Yet this simple procedure seems to be a rare thing many language classrooms, even when the subject is as clear a skill as pronunciation. That it is effective seems to be beyond question. Hattie (2012) stresses the importance of feedback, particularly disconfirmation feedback (Hey, you’re doing that wrong!), and Wiliam (2011) makes the case for embedded formative assessment that I found so compelling I did a series of posts on the book last year. Both of these authors are concerned with general learning and teaching. In the last year or so, however, I have increasingly come across papers and books that make the case for feedback in language learning, like this one from Derwing and Munro in Pronunciation Myths:

“Ample studies have shown that improved pronunciation can be achieved through classroom instruction…However, it is becoming increasingly clear that a key factor in the success of instruction is the provision of explicit corrective feedback (pg. 47).”

Not only is explicit formative assessment important, the claim is made that it is essential. Without it, that is under conditions of exposure alone, learning (improvement of pronunciation) does not seem to happen at all! Derwing and Munro mention two studies to back this up. The first is Saito and Lyster (2012) who managed to get Japanese students to improve with only four hours of training with the dreaded /r/ and /l/ sounds. The other is Dlaska and Krekeler (2013) who found that explicit instruction feedback was much more effective than just providing models. After years of don’t-disturb-the-learners-while-they’re-engaged directions, it seems that the role of explicit correction is finally being recognized.

You might argue that what the teacher I observed was doing was not that efficient or important. In cases, like EFL courses in Japan, where time is so limited, it may seem unreasonable to spend time on pronunciation, especially with the high importance of entrance exams and other high-stakes tests. Indeed many teachers argue that pronunciation is something they just don’t have time for. But actually, the teacher wasn’t spending much time on it at all. Most of the correction happened while the students were doing a reading fluency task (reading the text content multiple times). The teacher’s general comments and whole-class feedback/practice, took less than two minutes. Several years of similar feedback will undoubtedly have a positive effect on student pronunciation, student confidence, and student attitudes toward the importance of making the sounds of English reasonably accurately. In addition to the teacher’s feedback, student to student (peer) feedback could also be put to use. That will also help with sound discrimination training and meta-linguistic skill training.

Dlaska, A. & Krekeler, C. (2013). The short-term effects of individual corrective feedback on L2 pronunciation. System, 41, 25-37.

Saito, K. & Lyster, R. (2012). Effects of form-focused instruction and corrective feedback on L2 pronunciation development: the case of English /r/ by Japanese learners of English. Language Learning, 62, 595-633.

Does this Shirt Make me Look Fat? Motivation and Vocabulary

I love the topic of motivation in language learning (past posts here, here, and here, for example). In the world of TESOL, however, it’s a little like that old joke about the weather–everyone seems to talk about it but nobody does anything about it. In Japan, I often hear students voicing out loud how they wish they could speak English (even though they are students and even though they are enrolled in an English course at the present). They sound a lot like the people I know who talk about losing weight or exercising more: vague, dreamy, and not usually likely to succeed. TESOL research and literature talks a lot about integrative and instrumental motivation, ideal selves, and willingness to talk, etc., concepts that just seem so far from the practical reality teachers and those dreamy-eyed students really need. So in this post I would like to focus on the positive and practical and provide a list of things to do that improve the chances of success, drawing on formative assessment ideas and general psychological ideas for motivation.The idea is to approach motivating learners the same way one would go about motivating oneself to lose weight or start and stick to an exercise program. Instead of talking about fuzzy motivations, let’s focus on just doing it. The enemy in my sights is much the same enemy that faces the would-be dieter or exerciser, procrastination, a powerful slayer of great intentions.

First of all, let’s get one thing straight: you can’t do much about the motivation kids bring with them to your class on Day 1, but after that, you certainly can. What you and your students do together affects how they think and feel about language learning and themselves. That is, teachers can change attitudes by changing behaviors. And as a teacher, you have a lot of power to change behaviors. As BJ Fogg says, you shouldn’t be trying to motivate behavior change, you should be trying to facilitate behavior change.

Vocabulary learning is the perfect place to try out techniques for motivation success and overcoming procrastination because it is in many ways the most autonomous-friendly part of language learning. It can easily be divided into manageable lists, and success/failure/progress can be fairly easy to observe by everyone. It is also a topic I have to run a training session on this summer and I need some practical ideas for teachers to try out with their students.

OK, here we go. In addition to using teaching techniques that make the vocabulary as easy to understand and remember as possible, try the following:

- Make a detailed plan with clear sub-goals that are measurable and time-based. Break the vocabulary list into specific groups and set a specific schedule for learning them. This provides a clear final target and clear actionable and incremental steps, important tenets of formative assessment. Create a complete list and unit-by-unit or week-by-week lists. Be very clear on performance criteria for success (spelling, pronunciation, collocations, translation, etc.). Make the plans as explicit as possible, and put as much in writing as possible.

- Provide lots of opportunities for learners to meet and interact with the vocabulary. Learners need to actively meet target items more than 10 times each (and more than 20 times in passive meetings) if they are expected to learn them. Recycle vocabulary as much as possible.

- Create a system that requires regular out-of-class study (preview/review). Out-of-class HW assignments should start by being ridiculously small at first (tiny habits–see below), such as write out two sentences one time each. Grow and share and celebrate from there.

- Ensure success experiences. Success is empowering. The teacher’s job is to ensure that learners can learn and can see the results of their learning. Do practice tests before the “real” test, and generally provide sufficient learning opportunities to ensure success (“over-teach” at first if you need to). Lots of practice testing is a proven technique to drive learning, and students need to do it in class and in groups, and learn how to do it on their own.

- Leverage social learning and pressure. Have learners learn vocabulary together, teach and help each other sometimes, encourage each other, and just generally be aware of how everyone else is succeeding. Real magic can happen if a learning community puts its mind to something.

- Have learners share their goals and progress, publicly in class and with friends, family and significant others. Post results on progress boards, challenge and results charts, etc. At a very minimum, the teacher and the student herself should always know where they are and what they need to do to improve.

- Remind learners of the benefits of success. Provide encouragement, especially, supportive, oral positive feedback at times when it is not necessarily expected.

- Make sure that sub-goal success is properly recognized and rewarded. This provides a stronger sense of achievement.

- Make 1-8 as pleasant (fun, energetic, meaningful) as possible.

You may already be doing these things and still not getting the progress you hope for because the students just aren’t studying enough outside of class. Products of their age, they are driven by distractions–the need to check their Twitter feeds, for example, and the pressing issue of incoming LINE comments, or whatever. But they also suffer from the oppression of the same procrastination monster that we all suffer from. Oliver Emberton has a nice post on dealing with procrastination. For teachers, I would like to call attention to the last two items on his list of recommendations: Force a start, and Bias your environment. “The most important thing you can do is start,” Mr. Emberton writes. This is certainly true.

You can counsel them on the need to turn off their devices and “study more.” But unless you give them clear, doable, and manageable tasks and start them in class, and require and celebrate their use, it is unlikely they will get done. BJ Fogg recommends that you facilitate behavioral change by promoting tiny habits. His work makes the establishment of positive habits seem so much easier. You can watch an earlier overview of his method here, or a fun TED talk here. Much of what he describes can only be done by the individual learner, but as a teacher you can set the target habit behavior and you can help learners see the fruits of their newly established habits. Just choose a vocabulary learning strategy, reduce it to it’s simplest form, and provide a place to celebrate success. Then try to grow and celebrate the continued use of these positive habits. This modern world is a hard one to study in. There are really too many distractions too close at hand. It takes real strength, real grit, to resist them and start or keep at something new. Helping students to develop this strength and grit is now part of any teacher’s job description, I think.

If you are looking for more on how to teach vocabulary, including a nice section on web and mobile app tools that can help, Adam Simpson’s blog has a nice post on vocabulary. If you are looking for something that combines the latest in TESOL theory on motivation with practical techniques for the items I listed above, Motivating Learning by Hadfield and Dornyei is the best thing I’ve seen. It has 99 activities to choose from.

Has EFL Become ESL?

Years ago as a new teacher in Japan I learned very quickly to avoid materials that were not made specifically for Japan, very much a place where English is taught as a foreign language (EFL), a context very far removed from the English-speaking world. After a few painful slogs, I realized that, in particular, ESL (English as a Second Language) materials, or materials made to teach immigrants to England or Canada or the US, just wouldn’t fly in classrooms in Tokyo. They assumed too much background knowledge. They contained too much content. They were long. They assumed that students would be much more active–in learning, in giving opinions, in communicating. What worked instead was easy-to-memorize dialogs, short, focused worksheet exercises, and zippy little info gap speaking activities. In a system with low expectations for communicative success and limited opportunities for English use outside the classroom I guess we can say that it worked OK. At the time and for the most part, Japanese students didn’t especially learn English to communicate with people from other countries and cultures; they learned English to pass exams and to appear more international/educated/cultured to other Japanese.

A lot can change, however, when millions of people begin to travel overseas every year, record numbers of foreigners begin to visit, and just about everyone gets connected to the Internet. Indeed, the whole world changed. It has become, as this Economist article in 2009 suggested, much more difficult to find parts of the world that are not affected by the global movement of people and ideas. Japan included.

So what does this mean for English teaching in Japan? A lot, though you’d be hard-pressed to find changes in most jr. and sr. high school language classrooms in public education. A few teachers are making use of a few online resources, occasionally showing bits of Youtube videos for example, but most are oblivious to the fact that each student has in their pocket all the tools they need to learn English when they want to. The culture of learning is moving glacially, luckily for these teachers. Textbooks are still reassuringly analog, and teachers can still get away with explaining the content like mathematical formulas removed from wider communicative application. English is still being treated as a culturally distant “other,” needed in a certain way (mostly) for entrance exams, and otherwise put off indefinitely. And despite adding a few TOEIC courses, English conversation schools are still somehow managing to continue with a business model that basically sells access to native speakers, the same as they did in 1986.

But things are changing, make no mistake. Businesses are increasingly feeling the need to procure/cajole staff enough to double the number of people who can really function in English (from the 2012 level of 4.3% to 8.7% by 2017, on average) according to Diamond Weekly. And the larger the company, the higher the percentage. Companies with staff numbering over 2000 are generally aiming for having close to 20% of their workforce at a functional level (TOEIC scores over 730 at least). This is blowing back to public education, where there is increasing pressure to start teaching English earlier, and to start aiming kids at big proficiency tests earlier. In a Japan Times piece the other day, Osaka’s English Reformation Project is described. They are planning to put more emphasis on English, and more emphasis on the TOEFL test, believing that there is a global standard that needs to be accepted, and that Japan can no longer be an island that uses English in its own way for its own limited purposes.

Of course, real change will only come when certain present mindsets change: English must be learned in a formal institution; it must be learned from native speakers; you need to gain a certain proficiency level before you can begin using it for real communication; you prepare for entrance exams by cramming discrete vocab and grammar points; etc. Already we can see cracks. As the world continues to shrink, these cracks are likely to grow. Right now, if you can Skype and aren’t bothered by the accent of your conversation partner/teacher, you can begin practicing/learning English with a real live person for as little at 125 yen for 25 minutes. Similar services are sprouting up and there are more than a dozen companies ready to help you learn this way (not that you need a company, BTW), mostly making use of the large number of English speakers in the Philippines. The conversation school mentioned above doesn’t even have the Philippines on their map! But this, too, will change. The interactive multimedia do-it-yourself approach (as opposed to the go-to-the-bookstore-and-buy-a-book-written-mostly-in-Japanese approach, or the join-an established-conversation-school approach) has been slow in developing in Japan. But it is growing. It’s too pedagogically effective and cost effective to keep ignoring. Take a look at how some polyglots are making effective use of free web-based resources to learn any language they want.

So where is this post going? Well, the point I really wanted to make is that the the shrinking world is also driving a new way of conceptualizing English as a foreign language (EFL). With English on video, English on the radio, English podcasts, English groups and clubs, MOOCs, easy access to English books, and apps or websites available for any language learning detail you can imagine, does it make sense to assume that our students are really far removed from English-speaking opportunities and cultures? It may make sense to talk about English as foreign language as a starting point, but pedagogy should shift to recognize that English is no longer so, well, foreign. I have begun to think that all English teaching can now be thought of more the way that learning English inside English-speaking countries (ESL) has traditionally been defined. That is, what you learn in class, you can usually try out quite easily outside of class, if you have a mind to. Out of class time in EFL contexts can now be equally considered potential language use/exposure time.

I think this is one reason for the recent popularity of content and language integrated learning (CLIL, or content-based learning) in Europe and other places. This approach recognizes that English exists as a system of content and interaction that learners can plug into and work with. The idea is to create an immersive language learning environment in the classroom, wherever that classroom may be. This involves a rethinking of teaching and learning focus and goals, and more training for learning skills (such as discussion skills, presentation skills, and writing skills). If you are interested in further exploring CLIL or how to use rich tasks to facilitate better learning, I have two books to recommend. The first, on CLIL provides a good overview and rationale for this approach, while Pauline Gibbons’ book gets into the details of how to operationalize that in the ESL classroom, but as an EFL teacher, I found most of it attractive and applicable to the context in which I teach, a reaction I would not have had circa 1994. Click on the images for more information. The real question of what skills/language are most appropriate for the Japanese context is still being worked out, though. Test and test-prep schools have become so established that they cannot be ignored in any new approach. Certainly at the moment they are having a negative impact on learning English, at least for the purpose of enjoyment of communication and development of productive skills. A CLIL approach seems a interesting option, but it will require mindset changes, digital learning literacy; and cram schools and many entrance exams will have to redifine themselves.

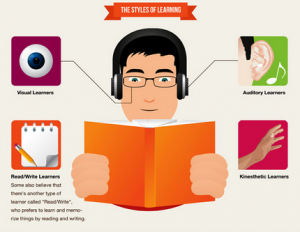

Learning Styles

One idea that comes up again and again is that of learning styles. Of course you have heard about it: some people are visual learners, some people have to hear things to learn them, and some kinesthetic people need to get their whole body into the learning process or nothing sticks. Google these terms–visual, auditory, and kinesthetic–and you’ll get enough hits to make you think that learning styles constitute an established theory in learning.

Unfortunately, that assurance would be misplaced. Daniel Willingham, in When Can You Trust the Experts?, has this to say:

…there is no support for the learning styles idea. Not for visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners…The main cost of learning styles seems to be wasted time and money, and some worry on the part of teachers who feel they ought to be paying more attention to [them]…(page 13).

This comes as quite a shock for many people because the idea is so entrenched. “Experts” talk about it often. It is mentioned in countless books and articles. I have heard it many times and repeated it myself. But, nope, it just ain’t so. There is no such thing as a “visual learner.” At least, there is no demonstrated effect in any scientific study. Mariele Hardiman summarizes the myth and the reality nicely in The Brain-Targeted Teaching Model. She cites Pashler et al. (2008), where you can read it yourself if you are still numb in disbelief (citation below). Hattie and Yates have a unit devoted to this myth if you are still not convinced. Great book, by the way.

But your intuition tells you that there are differences between learners. There most certainly are. Every brain is wired differently because of the individual’s experience and their age of development (for children). These developmental differences and experience differences are real and have very real consequences for how we should teach and the best sizes for classes, if we take differences seriously.

Essentially, differences take the form of preferences, preparation, motivation, and pace. According to David Andrews of Johns Hopkins University in the wonderful MOOC named University Teaching 101, students have preferences for the modality (yes, here we can talk about print or video or audio), groupings, and types of assessment and feedback. Students also vary in how prepared they are to learn. All learning involves connecting new knowledge to knowledge already held. If your students lack certain schema or factual knowledge, they will need more time to gain that and the target knowledge. In any given class, motivation differences (often because of prior experience) and time commitments can produce huge differences in the amount of attention and effort students will exert and sustain. Lastly, processing speeds (again because of experience and practice) in reading and auditory processing can make content more or less challenging than the instructor may think it is. Watch any class taking a test to see pacing differences in action. Students finish at very different times, and this is often unrelated to proficiency with the target content.

So, what should an EFL teacher do? Well, smaller classes are a start, but only if you are really planning to do something about it. If you are going to teach to the same middle as always, smaller classes will not necessarily give your students any benefits. Small groupings ranks only #52 in Hattie’s list of effective interventions, probably for this reason. Mr. Andrews suggests personalizing content and delivery as much as possible. He suggests getting to know your students as much as possible, and giving them as much choice as possible in how they learn. This is a delicate balancing act, in my experience. Students can be notoriously bad at understanding themselves, their strengths and weakness, and choosing better strategies. The teacher must push and pull them carefully up to better performance, offering them choices and checking that they are choosing wisely and making sufficient effort to see results. Technology can help a lot here. Recording short lectures/lessons and making them available with transcripts to students can allow slower/less-experienced/different-preference students options for learning and reviewing that can allow them to customize the education experience for themselves. And research has shown that repeated viewing/reading and multi-modal presentation are significantly correlated with better learning; and variety and choice will keep attention better and improve motivation. One crucial part of personalization is personalizing formative feedback (a series of posts on formative assessment starts here). The power of formative feedback in driving learning should not be underestimated, but you need to be close to your students to either do that yourself or teach them or their classmates to do it. This also involves making goals salient to students with clear rubrics, so that they can see where they are going and how they are progressing, and what they need to do to get better. A recent study in math classes at an American university illustrates this. For homework assignments, some students were given formative feedback and follow-up problems based on performance, while the spacing of content repetition was controlled for maximum effectiveness. This small change resulted in a 7% improvement on the short answer section of the final exams! Personalization seems to have that kind of power, if done right.

As Mr. Andrews says, “personalization has become a standard for learning in every part of our lives except school. And it will become a standard in school.” Get ready to hear more and more about it.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Roher, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 109-115.

Learning styles image fragment from https://www.home-school.com/news/discover-your-learning-style.php

Engagement and Motivation (Including Your Own): Dave Burgess Explains How to Teach Like a Pirate

One of the main forms of teacher training is the Super Teacher approach. Accomplished teachers give demonstrations for large groups of regular human beings who happen to also work as teachers, in order to inspire, demonstrate certain activities, or otherwise give hints for improved performance. It is a common approach and one that, as an EFL teacher trainer I can tell you, rarely seems effective.

Why? Because Super Teachers tend to be viewed as super humans with super specific skills that cannot be replicated by mere mortals: “It works for them, but I could never do that / or my students would never do that.” And because in a Super Teacher demonstration, we usually see a cherry-picked activity and have to imagine the process that led to it. It appears as a magic trick of an activity, the development of which is similarly left to the imagination.

Well, Dave Burgess is a Super Teacher, and a magician BTW, and he is well aware of these problems. I first heard about his “high-energy, interactive, and entertaining” workshops and presentations (take a look at this one, for an example), before ordering his wonderful, inspiring, little rollick of a book, Teach Like a Pirate. Yes, it did elicit the usual Super Teacher response, but it is much much more. The section on asking questions to explore your own creativity and maximize engagement and learning is worth…well, gold. He stresses (and then later shows) that ideas come from “the process of asking the right types of questions and then actively seeking answers.” It is a process that all teachers should be asking for everything they do and every activity they introduce. And the unit that focuses on presentation skills (“the critical element most professional development seminars and training materials miss”) is spot on. It is amazing to me that so many teachers do not see themselves as presenters, even though they stand in front of people most of the day, trying to get and keep their attention.

The book is roughly in three parts. The first one explains some general concepts and approaches and gives some examples. He talks about passion, enthusiasm, rapport, positioning material, the necessity of enthusiasm. It is a mishmash of theory and experience and made me nod politely in places and enthusiastically in others. The second part is the practical meat and potatoes of the book. He goes through a series of hooks that can be used to increase engagement. The beauty of this is not only in the nice collection of hooks, but in the way they are presented first as a series of questions: How can I gain an advantage or increase interest by presenting this material out of sequence? is the first of three questions for The Backwards Hook, for example. These questions engage you, allow you think up what you are already doing, and explore some things you might not have thought about. You’ll find many things you can’t or wouldn’t try, especially as a teacher in Japan who goes into the students’ room: food in the classroom, some of the decorations and costumes, and (in my case) dancing, crafts, and singing. But most could and should work, depending on how you envision them. A lot of them are pure gamification. Although Mr. Burgess is a history teacher, his ideas and the questions he poses are sufficiently adaptable for language teaching as well. The last part is clearly meant to be motivational, to push you to take the leap and try some of these things in your own classrooms now that your are fired up a little. As he says on his blog: Inspiration without implementation is a waste.

He has a website and a blog, but I did not really find them worth spending time at. It might be better to follow him on Twitter or watch some of his presentations on Youtube. Or better yet, keep pondering the questions in the book. The answers you come up with will decide the ultimate value of this Super Teacher’s book.