An article in the New York Times on the weekend called Can You Make Yourself Smarter?, mentioned the double n-back training that is being done to increase working memory (formerly known as short-term memory–Susan Gathercole can fill you in if you need an update on working memory). It’s a little long, but quite interesting, and a little controversial, too, it seems, as I found when I visited Larry Ferlazzo’s ESL/EFL Website of the Day blog, where he had posted his comments on this article (which he didn’t like) and another on exercise and the brain (which he did like–link below). I had stumbled across the double n-back a few months ago when I was doing a little research into working memory and the phonological loop, even trying the online version, which I recommend before you read the Times article or Larry Ferlazzo’s critique of it, or even before you read any further into this post.

Here it is, at a site somewhat appropriately labelled Soak Your Head. Go ahead, give it a try. I’ll wait……….

The Times article is more balanced than Mr Ferlazzo’s comments lead you to believe. The author, Dan Hurley (currently writing a book on intelligence, BTW), reports mostly on the finding of Susanne Jaeggi and Martin Buschkuehl, now at the University of Maryland, in a paper from 2008. They used the double n-back system to train people to improve their working memory and found improvements in their fluid intelligence as well. The claim that you can improve performance on a specific memory task doing it 25 minutes a day for between 12 to 17 weeks is not controversial. The claim that you can improve general working memory across the board is somewhat controversial. The claim that you can improve intelligence–reasoning, abstract thought, problem-solving intelligence–well, that causes a lot of controversy (see Randall Engle’s Attention and Working Memory Lab site for a truckload of blowback).

Many people agree that working memory capacity, especially phonological loop capacity, is critical to good performance at school, particularly for foreign language learning (see some of the many articles by Gathercole). But whether sitting at a computer screen for 25 minutes a day for what amounts to a semester of colored square and audio letter memory practice in increasing levels of difficulty (remember the last one; remember the one before the last one; remember the one 3 stimuli back) can help you, is questionable. It might help your working memory, but it is without doubt the closest thing to torture that I have ever seen in education. A person might elect to do it themselves, but I would not want to be responsible for imposing it on people, particularly at this time when researchers are finding different things.

But in Chicago they are doing it in a school system. And Torkel Klingberg, who invented the technique that later modified and did their experiments with, well, he formed a learning company and later sold it to Pearson Education. And all sorts of other researchers are moving ahead with similar projects to stretch working memory and improve intelligence. A lot of people apparently see something there… A lot of people also like the work done by Jaeggi and Buschkuehl, according to the article. They just seem to want to move in a slower and less grandiose way forward I guess.

One researcher mentioned in the article, Adrian Owen, is quoted as saying the following after his attempts to replicate J and B’s study:

No evidence was found for transfer to untrained tasks, even when those tasks were cognitively closely related”

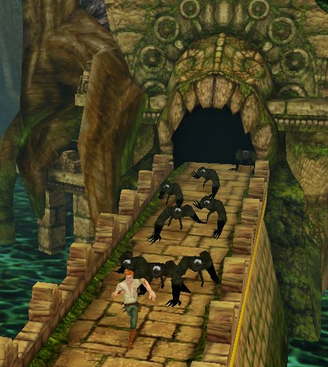

Yup, it’s the transfer problem again. You learn what you do in the way that you do it. I can think of a lot of other things I would rather my students be doing for 25 intensely focused minutes per day for 17 weeks. But I have to admit, I really wouldn’t mind if they went home and instead of playing Temple Run for two hours, they played for one and a half hours after they spent half and hour “exercising” their working memories. Or better yet, do aerobics for half and hour, stretch working memory with the double n-back for half an hour, and then run in the game like a madman for the last hour, with malignant demonic monkeys forever hot on your heels.

Jan. 2014 Update: Here is a Guardian article on the same topic. It covers some of the same ground (gaming, computer-based brain training), but also electrical stimulation of the brain, specifically the Fo.us headset. The article ends with advice to take Andrea Kuszewski’s advice and just try to challenge yourself more.

June 2017 Update: This study found no effect when training adults. Here is the reference: Clark CM, Lawlor-Savage L, Goghari VM (2017) Working memory training in healthy young adults: Support for the null from a randomized comparison to active and passive control groups. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177707