Gamification is a buzzword. Gamification is being widely–and often mistakenly–deployed in business situations recently. But because of the haphazard way it is being deployed and the mixed results it seems to be achieving, it is often viewed suspiciously by many in the world of business, and most in the world of education, where the very mention of games seems to suggest an offensive lack of seriousness. There are good and bad reasons to be suspicious of gamification, and it is not surprising that many game designers have hesitations about it.

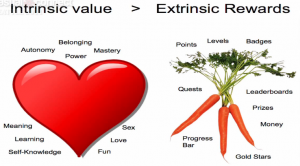

The main problem, as I see it, is that superficial features of gamification (especially points, badges, and leaderboards) are being applied without enough thought being given to the underlying cognitive and emotional constructs people –customers, employees, learners–bring to any situation. For education, gamification, game design, and user experience (UX) design present an opportunity to re-examine the mechanics and dynamics of motivation and behavior change. Yes, they apply to teaching, including language teaching.

The first post in this series looked at intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and rewards. My main point was that depending on the type of task or behavior, the use of extrinsic rewards–like many of the the tools of gamification–can help or hinder the development of intrinsic motivation. This is a critical point, but motivation is not the only factor in behavior change. So this post will focus on behavior change and the other factors involved: triggers, ability, and context. Yes, we are still in theoretical territory here, I’m afraid. But I promise to get more practical in future posts.

B.J. Fogg, a professor at Stanford U., is someone you might not have ever heard of if you are an EFL/ESL educator. He does not do research on motivation in education. Instead, his research is in how technology changes human behavior. And his main audience is business people involved in Internet-related start-ups, trying to get people to give their ideas or services a try. EFL teachers are often faced with a challenge that is really not so different from these young entrepreneurs: how do we get learners to engage in specific behaviors, in our case, ones that we know will help them improve in proficiency? High school students in Japan are limited in the number of classroom hours of English. They are limited by a lack of technology infrastructure in schools. They are limited by the priorities of schools that want more kids to pass certain university entrance exams. That means that a lot of lesson time is spent on teacher explanations of language that is too difficult for many learners in the room, and not enough level-appropriate input is given, and not enough meaning-focused output activities are attempted. One of the possible answers to this problem is in everyone’s hands–mobile devices. But learners have no idea of how to make use of them and teachers are really really reluctant to even try to get learners to do so, fearing accusations of unfairness, steep digital learning literacy curves, and chasms of technology coordination and control issues. And the whole undertaking would require a massive shift in educational culture to begin with. But, ah, if only it were possible…Teachers could flip lessons, focus more on engaging learners in tasks requiring language production, and concentrate much much more on giving good formative feedback on comprehension or skill development in class before the final summative tests. What I would like to suggest is that by making use of better design–and that almost certainly includes some game design techniques, but will also likely include user user experience (UX) design knowledge–we can increase engagement, push learners toward being more active participants in language learning, create a better learning experience, and hopefully get increased time on task and increased effort, and (eventually) increased target language encounters outside of class. Seriously, who wouldn’t want their classes to be more fun and more effective at the same time?

But before we get into the specifics of how gamification might be able to help with behavior change, we need to look at what Mr. Fogg has to say about changing behavior. There are, of course, other researchers working on habit and behavior change. But I think Mr. Fogg has the easiest to understand and most usable of ideas. As an introduction, let’s listen to the man himself summarizing his work: a short video is available on this page (sorry, the video is not embeddable into this blog).

Mr. Fogg sees behavior change as habit formation. His lab has produced a wonderful chart that lists the different types of change by whether it involves starting a new behavior, stopping a current behavior, or increasing/reducing a current behavior. He also distinguishes the duration of the behavior change, whether it is to be temporary (dot), for a fixed period (span), or lasting (path). For language teachers in Japan dealing with low-proficiency learners (in general, students at ‘lower-level’ schools tend to have poor study skills in addition to poor language proficiency), green span or green path behaviors are what we should be aiming at. Duh, you might say at this point. But wait, because the simplistic beauty of Mr. Fogg’s model starts now. For a behavior to change, 3 things have to be present: a trigger, the ability to do the behavior, and motivation. And the last two, motivation and ability, are trade-offs. That means if you have low amounts of ability, you need to have more motivation. If you have low amounts of motivation (which is usually the case for the learners in our target group), you need to make the behavior steps really small. According to Mr. Fogg, behaviors are always the result of sequences. But you need to think and plan them carefully to be sure they meet certain conditions. That is, you need to have an appropriate trigger while you target a doable behavior with sufficient motivation available. Here is another graph that visually represents this.

First, think carefully about the target behavior. Is it simple/easy enough? Do you have a trigger? Because you need one. In the classroom, triggers can be certain events. Set fixed activities in your routines that will act as triggers. One teacher I know has his students get out their dictionaries at the beginning of class for an activity that requires them. Like clockwork, the class starts and the students get out their dictionaries as the teacher writes the day’s three vocabulary items on the board. Target behavior: use dictionaries. Trigger: vocab activity at beginning of every class. Ability: getting out the dictionaries and looking up only three words is doable. Motivation: the students want to improve at English and the teacher has convinced them that using dictionaries is important.

Think about the current motivation your learners have. Is the behavior in sync with the learners’ goals? If not, you’ll need smaller steps, like in the dictionary example above. Target behaviors in small steps (Mr. Fogg calls them tiny habits). You really can’t go wrong making your steps really really small. Once one is established, you can target a subsequent behavior. An established behavior can be used as a trigger for another behavior. You can also go the other way and work on the motivation. Explain to learners why a behavior is important. Make the activity more desirable. Or make the behavior more attractive (fun, social, meaningful, etc.). But Mr. Fogg suggests focusing on ability and triggers. Keep in mind that although people will rarely do things they don’t like, it is sometimes the case that people come to like what they do, rather than do only the things they like.

Or leverage a context change. Changes of context are times when humans are more willing and able to lose existing habits or form new ones. So, plan your big changes from the beginning of the school year. Or if you are looking to establish some new behavior, such as pair or group work, reconfigure the classroom seating and move the desks.

Here is Mr. Fogg’s list of patterns for success. These points are well worth keeping in mind as you try to get learners to change behaviors.

“Help people do what they already want to do.”

“Put hot triggers in the path of motivated people.”

“Trigger the right sequence of baby steps.”

“Simple. Social. Fun.” (You must have at least two of these.)

“Harness the motivation wave to make future behavior easy.

“Simplicity matters more than motivation.”

Another presentation of his looks at common pitfalls of behavior change. I’ll embed it below for easier access.

Now that we have covered the theoretical ground, it’s time to look at the actual application of gamification mechanics. That will be the topic of the next post.

Also in this EFL gamification series:

Part 1: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards

Part 4: The Downside and How to Avoid It