Not everyone is enamoured with gamification. Jane McGonigal wrote an entire book about using games as a force for good and avoided the term completely. And if you google “problems with gamification” you’ll come across many pages encouraging caution or vitriol against gamification. And a lot of that is from some very smart people. Stephanie Morgan, a game designer like Ms McGonigal, actually called her Nov. 2012 presentation Gamification Sucks. She says what a lot of critics say: most commercial application of gamification is based on a “shallow and cursory” understanding of the concept. Her talk covers scores and points, achievements such as badges, and avatars, and if you have 30 minutes, it is both entertaining and enlightening. Points (and other components) have to mean something, she says. That’s the whole point. That’s the whole reason we might want to use gamification in the first place.

A very nice example of this can be found at the website Progress Wars. Please go there now and click until you get it. You’ll see. Go on then. This website makes very effective use of gamification techniques to make the effective point that it can be pointedly pointless (in a bad way).

Sebastian Deterding is one of the smart people I mentioned in the first paragraph. He has a couple of presentations online that address this issue. I’ll embed them below. The first one explains the problem with most gamification really well–how it is often misunderstood and how it can often have negative side-effects. The second one looks at the same problem from a user experience design perspective and gives some suggestions for avoiding pitfalls and making experiences more playful or gameful.

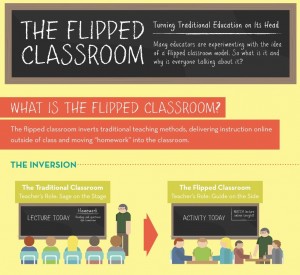

For teachers, the essential problem comes down to two things, I believe. The first is that there exists already a system in place at schools for delivering content and assessing mastery. If you try to add gamification to this system, there is a strong possibility that you will be seen as just sugarcoating, in which case you can cheapen your curriculum or quickly bore your learners. The second problem is that games by definition require voluntary participation. I touched on this in the last post, but this is really the big challenge for the teacher-designer. This needs to be addressed in several ways.

One is to understand the power of the feeling of self-efficacy. Learning and progress are fun. Put another way, “kicking ass is more fun.” But there must be real achievement.

“The more we analyze and reverse-engineer passion, the more we see learning and growth as a key component. No, not a key–the key. The more knowledge and skill someone has, the more passionate they become, and the more passionate they become, the more they try to improve their knowledge and skills” (Kathy Sierra).

No teacher would disagree with this. And yet many teachers fail to help learners see evidence of achievement. Without clear goals and generous feedback–from peers, from the teacher, from the learning system–learners cannot see improvement. And if they can’t see improvement then they can’t feel improvement, and motivation will not be sustained. It’s as simple as that. Games provide fantastic feedback and teachers must get used to making something like that part of the experience in the classroom. That means clear goals and regular formative feedback and meaningful markers of progress. Yet at the same time, there must be ample opportunities to try out new skills and knowledge in low-pressure (i.e., not tested) situations. A culture of trial and error until we see progress should be cultivated. Learners will put up with a certain amount of skill-building or knowledge collection if they see how it will help get them to their goals.

But while the key component is perceived growth, something has to happen to make growth happen. Revolutions don’t start when discontents reach thresholds of self-efficacy. Revolutions use the power and passion of ideas to bring people to the barricades, people who then build the skills they need. And that takes emotion. There needs to be more emotion, more delight, more meaning involved with moving through the material. My biggest shock from observing dozens of EFL classes in Japan was the total disregard for the emotional content of the textbooks. The teachers might as well have been teaching with phone books. Now, I have many problems with the EFL textbooks in use here, but the quality of the stories used is not one of them. These stories and the characters in them can be mined for empathetic meaning. But that is not all. The course itself becomes a narrative (as I covered in the Part 3). The learners are the heroes. The design of the syllabus, the importance of the goal, the journey, and the group–all of these can contribute to the emotional content of a learning experience. Emotional engagement must be there. So the key to teaching is to take neutral learners and make them care and work enough to see themselves grow in power. And then keep this going as long as possible with further challenges, further success, and further social support. But if that were easy, it would certainly be more common than it is now. The problem is the boring bits. And maybe games can give us some ides for how to do this better.

Games are not always non-stop action. Resource farming is a common feature of games. You undertake some sort of mostly mindless repetitive activity with the knowledge that you are growing or acquiring resources/skills/information that will help you ramp up, level up, or otherwise become more powerful in the future. Take a look at Plants vs. Zombie’s zen garden.

You just collect plants, starting with only one or two, very slowly adding more. And then you water, fertilize, and provide other care for them. You water one and the others want water. You have to repeat the process. Then you have to fertilize some. Then more. Then you have to go and buy more fertilizer and do it again. The plants generate money, but your first few little plants bring in so little that you wonder whether it is worth the effort. It’s very, very close to a production line job or one of those busywork assignments some teachers are so fond of. It’s boring but the plants are cute, and in the beginning you go along with it as you try to suss out the purpose. The plants generate money, you learn, but you have to collect it, which also takes up some of your time. Eventually, however, they start generating real money and you learn that you can use that money to buy cool new super plants or unlock certain special games. So eventually you learn that this busywork contributes to a better game experience–better performance at higher levels. But there is a hump that needs to be overcome. The same is true of a lot of EFL content, particularly vocabulary. To kick ass you need to know a lot of it. But it takes time to explore the elaboration of word information, and it takes time to perform the frequent rehearsals that acquisition requires (Laufer, 2009).. And I think students will come over that hump with you if they can see the purpose in it, if they can see how their power increases.

At first glance, it seems strange that the game contains anything as slow as the zen garden. Think about it: the game shamelessly includes a an activity that at first disengages you from the main play and then forces you to complete a series of tasks that are about as fun as washing windows, despite the humorous narrator and cute little plants. And it does this on purpose! I think it’s because the designers know that players won’t respect leveling up unless it comes with some skill improvement or some work. And the same is true of learners. They’ll accept the boring bits if they promise of rewards is real. But they’ll need some help–a clear goal, very, very clear feedback, a dash of emotion, and splash of fun.

Laufer, B. (2009). Second language vocabulary acquisition from language input and from form-focused activities. Language Teaching, Vol. 42, Issue 03, July, pg. 341-254.

Also in this EFL gamification series:

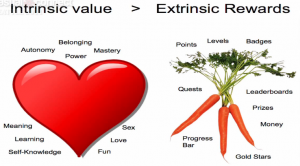

Part 1: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards

Part 2: Triggers, Ability, and Motivation