The present series of posts is looking at how EFL courses and classes in Japan might be improved by considering some of the techniques and activities emerging in ESL and L1 mainstream education settings. Previous posts have looked at goals, data and feedback, discussion, portfolios, and prolepsis and debate. The basic idea is to structure courses in accordance with the principles of formative assessment, so students know where they are going and how to get there, and then train them to think formatively and interact with their classmates formatively in English. All of the ideas presented in this series came not from TESOL methodology books, but rather more general education methodology books I read with my EFL teacher lens. I realise that this might put some EFL teachers off. I don’t think it should, since many of the widely-accepted theories and practices in TESOL first appeared in mainstream classes (journals, extensive reading, portfolio assessment, etc.); also, the last few years have seen an explosion in data-informed pedagogy, and we would be wise not to ignore it. In this post, however, I’d like to go back to TESOL research for a moment and look at how some of it might be problematic. Actually, “problematic” may be too strong a word. I’m not pointing out flaws in research methodology, but I would like to suggest that there may be a danger in drawing conclusions for pedagogy from experiments that simply observe what students tend to do or not do without their awareness raised and without training.

I’ve been reading Peer Interaction and Second Language Learning by Jenefer Philps, Rebecca Adams, and Noriko Iwashita. It is a wonderful book, very nicely conceived and organized, and I plan to write a review in this blog in a short time. But today I’d just like to make a point connected with the notion of getting learners more engaged in formative assessment in EFL classes. As I was reading the book, it seemed that many of the studies cited just seemed to look at what learners do as they go about completing tasks (very often picture difference tasks, for some reason). That is, the studies seem to set learners up with a task and then watch what they do as they interact, and count how many LRE (language related episode) incidences of noticing and negotiation of language happen, or how often learners manage to produce correct target structures. Many of the studies just seem to have set learners about doing a task and then videoed them. That would be fine if we were examining chimpanzees in the wild or ants on a hill; but I strongly believe it is our job to actively improve the quality of the interactions between learners and to push their learning, not just to observe what they do. None of the studies in the book seem to be measuring organized and systematic training-based interventions for teaching how to interact and respond to peers. In one of the studies that sort of did, Kim and McDonough (2011), teachers just showed a video of students modelling certain interaction and engagement strategies as part of a two-week study. But even with that little bit of formative assessment/training, we find better results, better learning. The authors of the book are cool-headed researchers, and they organize and report the findings of various studies duly. But my jaw dropped open a number of times, if only in suspicion of what seemed to be (not) happening; my formative assessment instincts were stunned. How can we expect learners to do something if they are not explicitly instructed and trained to do so? And why would we really want to see what they do if they are not trained to do so? Just a little modelling is not bad, but there is so much more that can be done. Right Mr. Wiliam? Right Ms. Greenstein?

Philps et al. acknowledge this in places. In the section on peer dynamics, they stress the importance of developing both cognitive and social skills. “Neither can be taken for granted,” they state clearly (pg. 100). And just after that, they express the need for more training and more research on how to scaffold/train learners to interact with each other for maximum learning:

“Part of the effectiveness of peer interaction…relates to how well learners listen to and engage with one another…In task-based language teaching research, a primary agenda has been the creation of effective tasks that promote maximum opportunities for L2 learning, but an important area for research, largely ignored, is the training of interpersonal skills essential to make these tasks work as intended” (pg. 101).

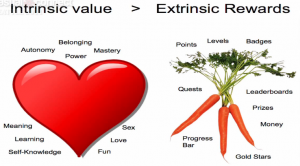

But not once in their book do they mention formative assessment or rubrics. Without understanding of the rationale of providing each other with feedback, without models, without rubrics, without being shown how to give feedback or provide scaffolding to peers, how can we expect them to do so, or to do so in a way that drives learning. Many studies discussed in the book show that learners do not really trust peer feedback, and do not feel confident in giving it. Sure, if it’s just kids with nothing to back themselves up, that’s natural. But if we have a good system of formative feedback in place (clear goals, rubrics, checklists, etc.), everyone knows what to do and what to do to get better. Everyone has an understanding of the targets. They are detailed and they are actionable. And it becomes much easier to speak up and help someone improve.

Teachers need to make goals clear and provide rubrics detailing micro-skills or competencies that learners need to demonstrate. They also need to train learners in how to give and receive feedback. That is a fundamental objective of a learning community. The study I want to see will track learners as they enter and progress in such a community.

Kim, Y., & McDonough, K. (2011). Using pretask modeling to encourage collaborative learning opportunities, Language Teaching Research,15(2), 1-17.