In 2013, I observed a sample lesson at a middle-level high school in Japan. The purpose was to demonstrate a style of lesson and convince the attending English teachers to emulate it. One of the targets of emulation was teaching English in English, and the other was teaching English communicatively. Dozens of English teachers from across the prefecture were there, dutifully and cautiously observing the sample lesson, in which a teacher managed to conduct a textbook unit explanation and lead a productive task almost entirely in English.

Few doubts or complaints were aired by the observing teachers. They know which way the wind is blowing. They know that the education board staff running the lesson observation/training have an agenda, and that agenda comes down from the Ministry: teach English in English; do productive tasks; teach communicatively. They understand that it is something that they should probably be doing, even though they did not experience this type of lesson themselves as students, even though they were never really trained to teach this way in college teacher training courses or on the job, even though they have doubts about their own English competence and are reluctant to put their shortcomings on display too much. So, they nodded politely, and promised to take the ideas back to their schools for further consideration.

Where, of course, it would be back to business as usual.

Nishino (2009) produced a paper that I still have trouble comprehending, but which I believe continues to sum up attitudes to teaching English communicatively in high schools in Japan. She found that Japanese teachers have pretty positive attitudes toward communicative language teaching (CLT), but mostly choose not to engage in it themselves. The reason, I guess, comes back to the lack of experience, training, and language proficiency on the part of teachers. But in my present position, it is my job to promote a greater use of English in the classroom by teachers and students, and that naturally involves more communicative activities.

For most Japanese teachers of English, however, this goes against their strengths, which often include techniques for grammar and vocab explanation, classroom management skills, and a proficiency with tasks that raise awareness of language features and encourage memorization. The CLT techniques my group (and the Ministry, and the BOE) are recommending often seem less than exemplary when observed in real classrooms, despite the authority of SLA research that stands behind the approach. This becomes painfully obvious when it is put on display, as in the class mentioned above, where the teacher had students write a short opinion about the topic and then share it with a partner and then the whole class. Even I couldn’t help thinking that the intellectual level was pretty low, and the pace was very slow. I’m sure many of the teachers observing with me had the following thoughts going through their heads: this is dumb and really inefficient.

And this brings me to the main point of this post. The dabbling with CLT that I have seen in classrooms here makes me wonder if it is worth the effort of teacher awareness raising, of teacher skill training, particularly if we see it as a goal unto itself. It seems that a little more CLT in classrooms is unlikely to make much of a positive difference in language classrooms. Students don’t seem especially more engaged, and the trite bits of incorrect language that often get produced are depressing–and are often incomprehensible to other students without a quick translation from the teacher. I know that the system is failing pretty much at producing kids who can use the language right now. But I don’t think the fix will come with a few more CLT activities and a strict English-only policy on the part of teachers.

Of course, the answer cannot be business as usual either. Teachers have been yakking at students for years, explaining and translating, and that hasn’t worked out well at all. Van Patten (2014) in Interlanguage Forty Years Later, is particularly blunt in his assessment of the teaching of language by the teaching of rules, the kind most common still in Japan: “competence is not derived from explicit instruction/learning…[and that] holds true for all learners and all stages of development…” (pg. 123). Yes, instruction gets you something, but it is not competence. Form-focused instruction is very limited in what it can do for language learners, that much seems obvious to everyone–well, almost everyone….

So what it is the answer? I’m not sure, but more language, more language use, and more focused teaching seem to be the only way forward. Standing in the way, though, are the lack of proficiency of teachers (along with their lack of training/familiarity with alternative approaches), the culture of expectations that makes change difficult (the parents, the cram schools, the perceptions of entrance exams, the publishers, etc.), the passivity of students and their unfamiliarity with the kind of active use of the language needed to leverage learning, and the well-meaning souls whose hearts warm satisfactorily when students produce any kind of utterance (even when it is intellectually low, and mostly incomprehensible). Framed another way, what we need is more language processing and more responsibility for doing so in a comprehensible and academically appropriate manner.

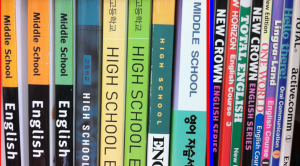

The image above (from a presentation on vocabulary by Rob Waring) shows a bookshelf with Korean English textbooks on the left and Japanese ones on the right. Notice the size difference? That translates to Korean students being exposed to thousands of words more during their years in mandatory education. The poverty of input argument for Japan is pretty easy to make if we look at just the amount of language students are exposed to, compared to Korea or Mexico (as Mr. Waring did), both of whom now handily beat Japanese scores on high stakes tests (TOEFL iBT, 2013: Japan 70, Korea 85).

There may be other reasons why Korean TOEFL test scores are higher. But certainly language exposure is one of them. Perhaps it is time to admit that in Japan, teachers explain too much in Japanese about too little target language. Adding a little “communicative” jibberish to that is unlikely to make a big difference, and may actually be detrimental in the long run if it lowers expectations further. In my opinion, more language immersion in the form of CLIL-type lessons at the high school level might be an interesting option to explore , since it provides CLT with sufficient input, thinking rigor, and responsibility.