This is the second in a series of posts on motivational effects that have proven both enduring and contentious. The first post looked at the Hawthorne effect.

But before we get into the second effect, let’s try a little thought experiment. A student, let’s call him Sue, has a mother who complains all the time that teachers just don’t challenge little Sue enough. It’s their low expectations that have caused him to be the perpetual underachiever that he is. Sue’s mother is convinced of this because the teacher seems to lavish praise and attention on Darla who gets perfects on tests, loves to volunteer answers in class, and will no doubt one day be valedictorian. Ready for the experiment? Quick, design an experiment that might prove or disprove that the teacher’s attention and expectations are in any way responsible for the performance of the two students.

And there we come to the problems with the Pygmalion effect, the notion that when greater expectations are placed on learners, they perform at higher levels. It seems so intuitively true. At the same time, however, it is really really difficult to isolate the variables and demonstrate it objectively. Can we really prove causation? And does the effect compound over years with different teachers? If not, is it lasting? The effect is also sometimes known as the Rosenthal effect after Robert Rosenthal whose early experiments helped to get the effect recognized. His book, first published in 1968 and then updated in 1992 certainly helped to popularize the term and link it with the effect. Other names often heard are self-fulfilling prophecies or expectancy effects, the plural being significant here in order to include the effects of both positive and negative expectations. Rosenthal’s work seems to be a good place to begin, but first let’s consider the origin of the name.

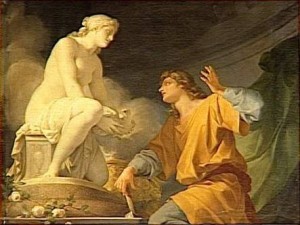

Pygmalion was a sculptor who fell in love with a sculpture he made. According to the myth, recounted by Ovid, he is so in love with the statue that Venus eventually takes pity on him and sends Cupid to bring her, Galatea, to life. Pygmalion and Galatea get married, have a son and live pretty happily ever after. This story is the source of countless poems, stories, plays, and movies, most famously Pygmalion by Shaw (later adapted as My Fair Lady for Broadway and film). The main point here is that the teacher is a creator and the more he–let’s stay with the gender of the story–puts his heart into his work and the higher his expectations are for his charges, the more they accomplish, be it love, life, happiness, or a 27.4 IQ point gain.

The Oak School studies by Rosenthal and Jacobson showed that teacher expectations matter, especially for younger or newer learners (when the teacher has not yet had a chance to form an opinion of expectation). Basically, teachers were told fabricated results of students on a standardized achievement test. After a year, the students who had reportedly scored really high on that test were doing better in their classes, thanks to the higher expectations of the teacher. Rosenthal and Jacobson measured IQ gains and there are reasons to be suspect of their methodology and findings, but Rosenthal is adamant about the existence of a Pygmalion effect. The findings of this study and several others by Rosenthal, as well as their implications for teachers and administrators, are nicely covered in this short article.

In a more recent overview of 35 years of Pygmalion studies by Jussim and Harber (2005) a more sober view of the research into self-fulfilling prophecies can be found. The findings are summarized as follows:

“(1) Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom do occur, but these effects are typically small, they do not accumulate greatly across perceivers or over time, and they may be more likely to dissipate than accumulate; (2) powerful self-fulfilling prophecies may selectively occur among students from stigmatized social groups; (3) whether self-fulfilling prophecies affect intelligence, and whether they in general do more harm than good, remains unclear; (4) teacher expectations may predict student outcomes more because these expectations are accurate than because they are self-fulfilling.” (pg. 131)

It seems that recent research seems to be focusing on race, gender, and social stigmatization and the role of teachers in perpetuating social discrepancies (see work by Rhona Weinstein, for example). But what about individual learners? Is the effect of teacher expectations really “unclear” or “small”? Work by Dweck (Mindset, 2006: click here for my review) seems to suggest that what and how a teacher does in the classroom can make a big, clear difference. Praising effort rather than accomplishments can lead to considerably more future effort and eventually much greater success. So it seems likely that expectations (of effort, of success) have some bearing on that. I for one would not be so quick to dismiss the findings of Mr. Rosenthal just for procedural reasons. But the interaction between teachers and students is complicated and dynamic and it may be difficult to draw actionable conclusions. In any case, it would seen prudent to always expect more from learners. Of course, one has to believe that improvements are always possible. For me, research into brain plasticity and how people become experts has helped me to strongly believe in the potential of each learner. I also try to get my learners to understand that talent is not necessarily something they are born with, which takes some doing usually because the belief in innate talent is really pervasive.

Perhaps a more disturbing possibility that we can take away from all this is the one that Japanese learners of English belong to a group that is stigmatized, that is, expected to fail when it comes to English, if I may extrapolate a little from finding (2) in Jussim & Harber. It has often struck me as strange that students who cannot string three words together in English by high school are not considered unusual, but a student who, say, cannot multiply 8 by 9 in junior high school would cause a major freak-out. There are different standards for different subjects. The (particularly communicative) expectations for English learners in Japan are painfully low and that needs to change. If work by Weinstein is any indication, it will require considerable time and effort to effect such change.

Jussim, L. and Harber, K. (2005). Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review 9, 131-155